Join Feminist Majority Foundation intern Serena Saunders each week in If I Were a Rich Man as she explores the topic of money–as it relates to feminism–to provide young people with the information and resources they need to survive, thrive, and fight economic injustices. This week, Serena’s tackling a new federal rule on subcontractors and franchise employees, and how it could change the lives of millions of workers for the worse.

The Basics: NLRA, NLRB, and Unions

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) was enacted in 1935 to encourage “the practice and procedure of collective bargaining and by protecting the exercise by workers of full freedom of association, self-organization, and designation of representatives of their own choosing, for the purpose of negotiating the terms and conditions of their employment or other mutual aid or protection.” In plain-speak: the NLRA ensures government protection of unions. While unions had existed prior to 1935, the NLRA wrote both the right to collective bargain as well as protections from unfair labor practices into U.S. law.

The NLRA created the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the independent federal agency that sees out the enforcement of the NLRA. Currently, the NLRB:

- Provides the framework for union elections,

- Decides cases,

- Facilitates settlements,

- Investigates charges, and

- Enforces orders.

It also–critically–implements broad policies that impact entire sectors of employees and the processes that govern their bargaining, going beyond regulation and oversight of individual unions and employers.

But wait–what’s a union?

Unions are organized groups of workers in a company or field of work who band together to fight for their rights and interests, like wages, benefits, and working conditions.

New Rule: Joint-Employer Status

“Joint-employer status” determines who is responsible for bargaining with unions over “essential terms and conditions of employment” when more than one employer is involved.

Imagine a temp agency where Company A officially hires someone but assigns them to work at Company B. Or picture a fast-food chain (Chain X) that has a local franchise (Restaurant Y). The NLRB’s decisions on joint-employer status says who is responsible for employees’ wages, benefits, hours of work, hiring, discharge, discipline, supervision, and direction, which are the eight newly-defined essential terms and conditions of employment. In the temp agency scenario, which company–A, B, or both–is beholden to the NLRB’s rulings? In the hypothetical restaurant chain situation, is Chain X or Restaurant Y responsible for improving employees’ work lives?

The NLRB has waffled back and forth for years as to which entity is responsible for employees in joint-employer status situations. Before 1984, both employers were held jointly responsible for responding to collective bargaining, strikes, and unfair labor practices; however, two 1984 decisions narrowed that significantly–essentially, saying that only the most direct employer (i.e. Company B and Restaurant Y) had to interface with unions, while the more indirect employer (Company A and Chain X) could avoid that responsibility. 2015’s Browning-Ferris decision returned joint-employer relations to its pre-1984 status, giving hope to many employees trying to organize their subcontracting and franchised workplaces.

But a new rule released by the NLRB on February 25 rolled back Browning-Ferris’ protections for workers by returning to the narrowed scope of joint-employer status. This rule mirrors recent rules around joint-employer status from both the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Department of Labor. This means that workers in joint-employer scenarios cannot directly confront their larger employer, only the smaller employer more directly related to them. Once again, it’s more difficult for workers to organize, bargain, and succeed in fighting for their rights. It also means that it’s easier for large employers to shrug off responsibility for employees that their bottom line depends on: the rule creates an incentive for employers to subcontract out and work with franchise owners in order to reduce their own liability.

Today, the Trump NLRB issued a new joint-employer rule.

— Fight For 15 (@fightfor15) February 25, 2020

We’ll continue joining together and speaking out until @McDonalds acknowledges its responsibility for workers like me instead of hiding behind the fiction of a franchise system it pioneered to screw us over.#FightFor15 pic.twitter.com/MlP55lrTpg

Why Is This a Feminist Issue?

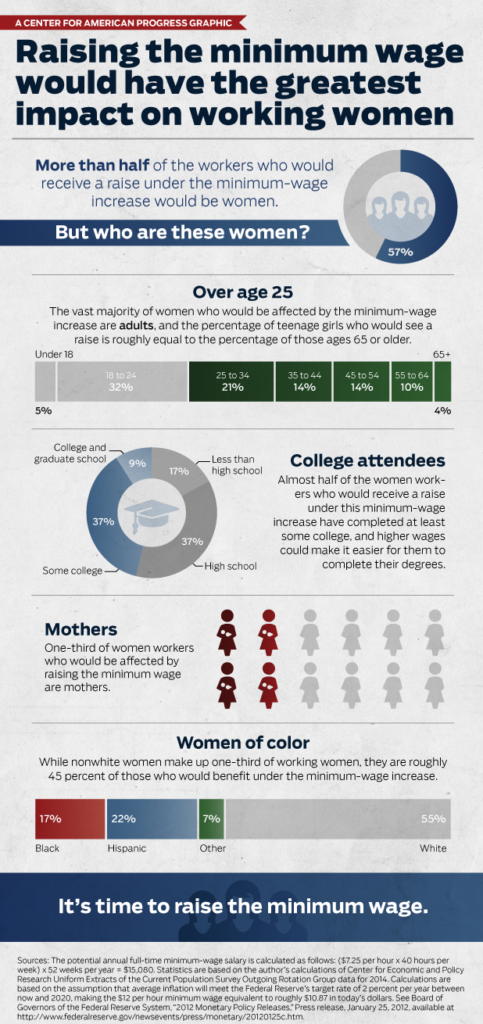

Women are generally over-represented in the low-wage workforce, defined as jobs that pay less than $11 an hour, like fast food workers, restaurant servers, cashiers and maids. Plus, women are typically paid 15 percent less than their male counterparts in such jobs, with additional pay gaps based on race.

Consider McDonald’s. The fast food chain has about 14,000 restaurants in the United States, franchises making up 12,600 (or 90%) of them. The McDonald’s mega corporation has washed its hands of responsibility for its workers, leaving the restaurant’s franchisers responsible for the thousands of McDonald’s workers running each individual storefront.

In 2012, McDonald’s workers accused the multi-billion dollar corporation of union-busting, the illegal and unethical practice in which employers retaliate against employees attempting to bargain collectively through the establishment of a worker’s union. Workers banded together to create Fight for $15, an organization dedicated to ensuring a living wage (McDonald’s currently pays its employees $9.91 an hour on average) and the right to a union, with particular focus on McDonald’s and other low-wage employers. McDonald’s has also been accused of sexual harassment, with several high-profile cases over the past few years and some claims resulting in a 2018 strike.

Under the new joint-employer status rule, it’s going to be difficult for workers to effectively come together to organize a powerful union against McDonald’s as a whole, because they’ll be limited to working against their particular franchise location. If they do manage to create a union, their wins will be franchise-specific, not binding the entire company by agreements that can and should include higher wages, better benefits, an end to sexual harassment and more. The women who make up the majority of McDonald’s employees — and other low-wage, subcontracted or franchised workers — will have a tough time fighting their employers to better their lives due to the NLRB’s decision.