Join Feminist Majority Foundation intern Serena Saunders each week in If I Were a Rich Man as she explores the topic of money–as it relates to feminism–to provide young people with the information and resources they need to survive, thrive, and fight economic injustices. This week, Serena’s exploring the effects of not having paid sick leave on efforts to fight coronavirus.

What’s Paid Sick Leave?

Paid sick leave is a policy–varying from employer to employer–permitting workers to take time off from work to address their own health condition(s) or the health condition(s) of their loved ones, while still earning all or some of their pay. With paid sick leave, workers can prioritize their health and the health of those around them instead of worrying about losing their job or not being able to pay their bills. Currently, there’s no federal law requiring paid sick leave for workers, but twelve states and Washington, D.C. require employers to provide paid sick leave to employees and many private employers voluntarily include in their benefits package in order to remain competitive and attract top talent. As of March 2019, one in four workers had no access to paid sick leave–including 6% of the highest earners and two-thirds of the lowest earners. 40% of workers in the service industry–including childcare, restaurants, and retail–have no paid sick leave.

Paid sick leave means workers don’t have to go into work when they feel sick or are caring for a loved one who is. Related is paid family leave, which allows time off to care for a newborn, newly-adopted, or newly-placed child.

How is Paid Sick Leave Related to Coronavirus?

The coronavirus, formally known as COVID-19, has officially been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). Cases around the globe are being handled in different ways by different countries, and many countries are handling the crisis on national levels. As of just this past Friday, March 13, at the very end of the work day, a deal was finally reached between the president and Congress to provide funding and policies to mitigate the spread of the virus, including emergency paid sick and family leave.

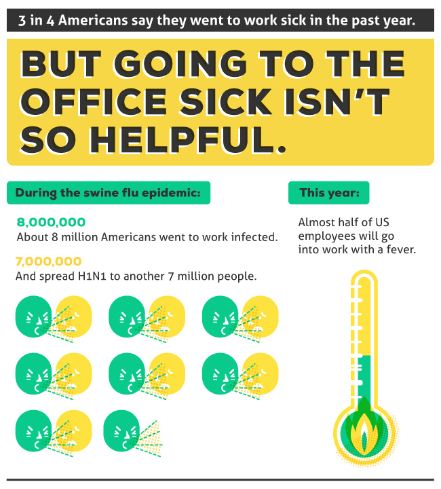

One simple solution touted by many is for people to take action at the individual level: anyone who thinks they’ve been in contact with infected individuals or have any symptoms indicate of the coronavirus should stay home from work and self-quarantine. (A quarantine of up to two weeks is recommended for those exposed to the virus.) Unfortunately, given the widespread lack of paid sick leave—especially in service jobs, where person-to-person contact is high—that’s not an effective recommendation.

Democrats in the House and Senate introduced a bill for emergency paid sick leave on Friday, March 6, but the proposal hit a wall in the Republican-controlled Senate. Less than a week later on Thursday, March 11, House Democrats proposed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, a mega-bill intended to provide support to affected families; it includes “paid emergency leave with both 14 days of paid sick leave and up to three months of paid family and medical leave.” As the outbreak worsens, the plan has once again been jammed in the Republican-controlled Senate.

Why Is This a Feminist Issue?

The negative effects of the lack of paid sick leave on the fight to mitigate COVID-19 disproportionately fall on low-wage (less than $11/hour) and service workers, who tend to be women. About two-thirds of women in low-wage jobs are single, and 32% of women in these jobs have one or more children in their household. Women make up more than 75% of workers in education and health services; 51% of workers in the leisure and hospitality industries; and 52% of workers in “other services,” which includes private households and laundry services. Disparities also exist across racial lines as Black and Latinx women are more likely to work in lower-paying service jobs, creating further issues in access to economic support.

All of this means that lower-paid women of color in the service industry are among the most likely to face issues like eviction, homelessness, and bankruptcy because they couldn’t take paid time off of work to care for themselves or their families. Add coronavirus into the mix and it creates a deadly multiplier effect: those who may have been exposed to the virus via interactions with customers and other workers still must report to work—out of fear of not earning money or losing their jobs—and are at higher risk of getting sick from the contagious disease–then they will likely infect others. It’s not only an economic issue, but a public health one.

To put it simply: “If we work sick, then you get sick,” workers chanted during a New York City protest.