September 20, hundreds of thousands of students from schools across the country participated in the Global Climate Strike. The strike, led by climate activist Greta Thunberg, started summer of last year near the Swedish parliament to urge world leaders to take immediate action to combat climate change. What Thunberg started as a one-person strike in Sweden soon received national and then international attention, forcing the climate issue into urgent and mainstream discussion. Following the Global Climate Strike, Thunberg gave a very moving speech at the United Nations, telling world leaders,

You are failing us [the younger generation]. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you fail us I say we will never forgive you.”

Greta Thunberg

Climate change–and the consequential prospect of having no real future– has led to severe anxiety among young people. “A lot of us say we can’t think more than 16 months ahead because we don’t know the environment we will have to grow up with,” said Madison, Wisconsin climate activist Max Prestigiacomo. Scientists have dubbed this type of anxiety “climate grief,” “climate anxiety,” and “eco-anxiety.”

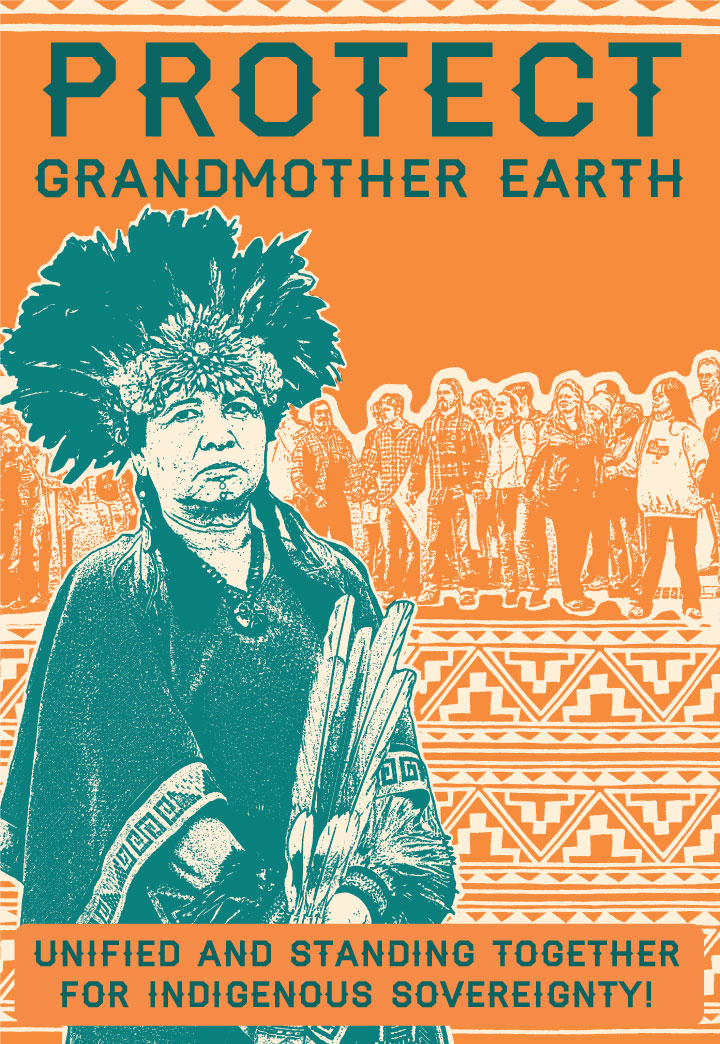

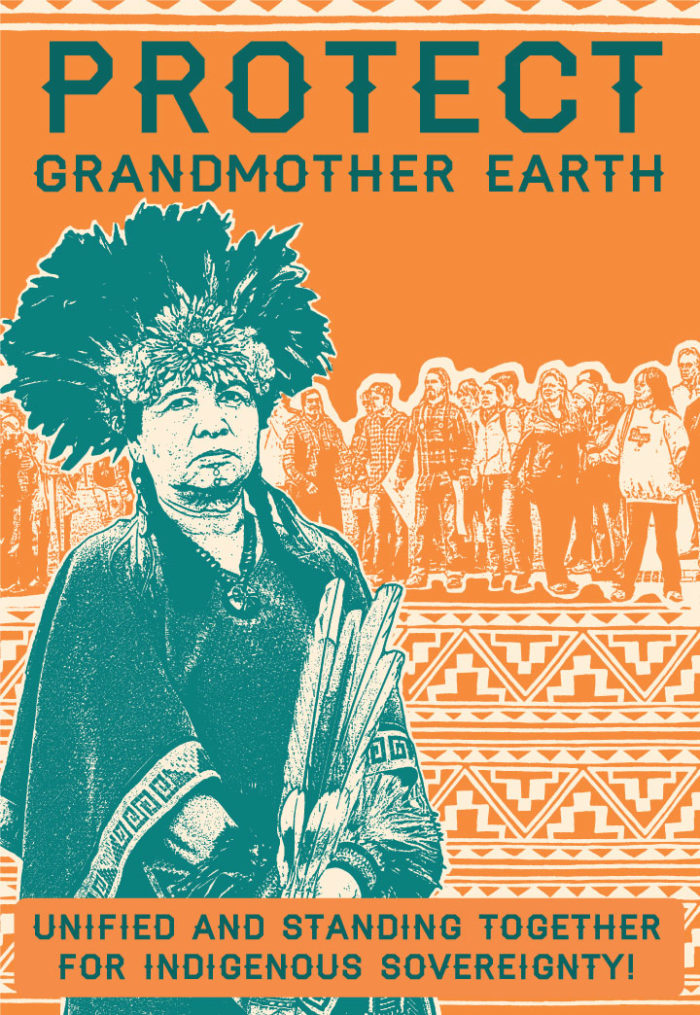

The narrative around climate change is continuously produced in the future tense. It is portrayed as a pertinent threat that is going to come and something that will disproportionately affect younger generations. However, by listening to the voices of a select group of activists, international and local organizations make the mistake of whitewashing the climate problem. Preserving the planet and saving it from real threats of industrialization and capitalism have always been key for marginalized people, specifically the Indigenous community. American nation-states that have been founded on occupied Indigenous land have established institutions that systematically exploit natural resources key to Indigenous cultures and livelihoods.

In particular, Indigenous women have become key targets of land development and industrial projects. According to a study published in February of this year, around 6,000 Indigenous women were reported murdered or missing in 2016; according to activist Ruth Miller, these incidences of violence have been concentrated around land development projects. Native American feminist activists like Winona La Duke have long emphasized the intersection between climate justice and gender justice, especially within Indigenous communities.

Adhering to current national and international climate reforms may or may not make us effective allies to the environment and to marginalized communities. Compliance with the Paris Climate Agreement was one of the Global Climate Strike’s main demands, but the document has been criticized by other activists as not effectively centering the lived experiences of those most impacted by climate change. One clause of the agreement in particular, the carbon trading clause, is problematic because it allows industries to continue burning fossil fuels and exploiting land. As we have repeatedly witnessed (think #NoDAPL), due to a lack of protections Indigenous land usually becomes the most vulnerable to exploitation by big companies.

We need to create more safe spaces in the environmental movement for underrepresented communities and learn from them as to how we can be better allies. It is time we collectively work towards ending our complicity in the continued oppression of marginalized societies: the voices of Indigenous women must be heard in the mainstream climate movement.